Monday, 19 December 2011

Thursday, 17 November 2011

Like a litter of newborn mutant babies painfully slithering out from a womb, words surfaced: “Entropy… entropy… chaos… chaos… children… entropy… chaos…” Something about the inflection of the word “entropy” when it formed in his head after “children”, a subservient, almost worshipful tone.Equal parts Ligotti, Lynch and his own special brainbrew weirdsplosh, my friend Suresh Subramaniam's deeply unsettling tale, 'Bharath's Toys' can now be read at Pratilipi.

The same issue contains my own story 'Empty Dreams'.

Tuesday, 1 November 2011

law

Henceforth, nobody who has written and had published a novel (a) in the 60s and later that is (b) not a genre novel (crime, SF, fantasy, horror) should be permitted to share with the world a non-fictional essay or pronouncement on art, literature, politics, childlessness, childbirth, culture or clashes thereof, humanity, animals, insects, birds, reptiles, mammals, trees, flowers, fungi, fjords, airline ticket prices, aesthetics, atheism, religion, ravines, valleys, hills, mountains, poetry, prose, reality, fantasy, dream, memory or indeed anything at all whatsoever. It just makes them look stupid.

The genre writers can write what they like. No one will pay attention.

The genre writers can write what they like. No one will pay attention.

Friday, 28 October 2011

the awful truth

I fear for my sanity.

The things I have seen would make a stronger man weep like a little child and scream like a banshee who has caught her thumb in a doorjamb.

It all began that fateful day when, immersed in my studies, I stumbled over the threshold of the Forbidden Manuscript room in my college, Miskatonic University. I wasn’t much for the musty old scrolls and tomes in there; structural engineering was more my line. But, having wandered in, something about the timeless, eerie atmosphere in the room made me linger. I strolled here and there, perusing hoary old alchemical almanacs and occult treatises, things with long, Latinate titles and illustrations of strange geometrical forms and demons with quaint little horns and tails.

Then, I stumbled upon the dreaded Necronomicon, that fabled compendium of the most unhallowed secrets of space and time, written by the Mad Arab, Abdul Al-Hazrad, he whose name is abomination to this very day. With my analytical mind and speed-reading techniques, I rapidly realized that even this text was only a gateway to another, more diabolical secret book; an Unholy of Unholies. The Book Of The Djinn.

I do not know what spark of madness had slumbered all these years in my rational, workaday mind, waiting to be fanned into a raging flame of obsessive insanity. Perhaps there was some flaw in the physical structure of my mind, perhaps some loathsome practitioner of dark arts lurked in some distant branch of my family tree, perhaps my mother dropped me on my head as an infant while laughing out loud upon perusing the horoscope section of the newspaper; I shall never know.

I do know that, from that moment, I could not rest until I had to read The Book Of The Djinn. Thus began a decade-long quest that took me from my native clime to the furthest reaches of the globe, from a cattle farm in Central Africa to an abandoned mine in Rhodesia, from the icy northern shores of Iceland to the Japan Sea and beyond.

Finally, I found the tome I sought in a cave high in the Himalayas, amidst barren rock and thick snow. Three chambers did I uncover, smashing stout doors of an indefinable substance to pass within, before at last I entered into the fourth, innermost chamber. Without pausing to explore the outer chambers, I read the long-sought-after book. I found therein a tale of the utmost brutality and strangeness, a tale of three beings, known collectively as The Djinn, although they had nothing in common with the Arabic imps who go by that name. These were three creatures of vast, cosmic evil whose very existence proved that the universe was little more than a largely empty bag of swirling molecules, governed ultimately by chaos but momentarily by three savage beings who stood atop the eldritch pantheon already revealed in the Necronomicon, lying dust-covered back there in dear old Miskatonic University.

They were: The Hitter Of Things; a massive, powerful creature who sought to remake the universe to the rhythm of his own percussive assaults. The Rumbler Beneath: a conniving, insidious behemoth who tortured the very fabric of reality with his subsonic imprecations. The Bellower Of Abomination, a colossal leviathan, crooning and ululating foul words of madness and ultimate disruption.

My fear and misgivings grew stronger and stronger as I learned how even Hasthur and Cthulhu had joined hands to chain these three terrible creatures in some fastness tucked away in a then-obscure corner of the universe, high atop a snow-capped mountain. A strange sense of déjà vu overcame me and as I compared the symbols in those ancient pages with the etchings on the doors I had so carelessly smashed through, I realized the awful truth.

I had released the Three Most Dread, unleashed them on an unsuspecting universe.

I fear for my sanity. I fear for my life. I know that they are sending their minions to deal with me even as I write these words.

I beg of you, heed my words and learn from them.

I beseech you, do not listen to their songs of madness and dissolution.

I implore you do not listen to

Djinn & Miskatonic.

Djinn & Miskatonic is:

Gautham Khandige: Vocals

Jayaprakash Satyamurthy: Bass

Siddharth Manoharan: Drums

We bring together fuzzy bass, dramatic vocals and kickass drumming to play songs that channel influences from Black Sabbath, Electric Wizard, Sleep, Hawkwind, Neu!, Soundgarden, Reverend Bizarre, Cathedral, St. Vitus, Melvins, The Tea Party, Joy Division, Eyehategod and more into a primitive, groovy, heavy, spacey assault of droning doomoid rock.

You have been warned.

Wednesday, 19 October 2011

I am zombie and so can you

My band Djinn & Miskatonic's first gig is on monday.

Here's one of our songs: I Zombi

Recommended for fans of: slowness, heaviness, minimalism, Fulci, Lewton and La Noche del terror ciego

Here's one of our songs: I Zombi

Recommended for fans of: slowness, heaviness, minimalism, Fulci, Lewton and La Noche del terror ciego

Labels:

fuck you i'm a musician

Monday, 3 October 2011

I could go there

He was something like an emperor

Something like a hero

He chose a path; he was destroyed

He was something like a friend

It's lurking, a cleaner world

A neater world, sparse and silent

It's waiting to pounce

Pain measures the distance you travel

A single incision after a pitched chase

A moment's shuddering; release

Or die for days after falling

Terrible infinite surfaceless seconds

I wish I could use his remains

like the man in 'Rogue Male'

Make a weapon, fight the killer

Vengeance, a vain chance

I wish I could freeze that frame

I wish I could hold those seconds

Or days in my mouth

Feel cold salt dissolve on my tongue

It's a neater, cleaner place

Sparse, silent and free from despair

I could go there and be with you

If I only had the measure of pain

Labels:

fuck you i'm a poet,

fuck you im a poet

'You bite into an apple and find a worm in it. You throw the apple away.

But what if the worm could make itself look like part of the apple?

What if the worm could make itself look like the apple?

What if the worm could make itself look like many apples, like an apple orchard, like a man walking through the orchard, plucking an apple, biting into it, finding a worm, discarding the apple?

What if it's worms all the way down?'

- from the Ouroboros apocrypha

But what if the worm could make itself look like part of the apple?

What if the worm could make itself look like the apple?

What if the worm could make itself look like many apples, like an apple orchard, like a man walking through the orchard, plucking an apple, biting into it, finding a worm, discarding the apple?

What if it's worms all the way down?'

- from the Ouroboros apocrypha

Tuesday, 27 September 2011

2 quick thoughts tata see you later

I am saving pennies (paisas actually) for when the inevitable Hard Case Crime/Mills & Boon crossover books to start appearing.

I also think it's dangerous to be mystical unless you see it as metaphorical in which case it's a lot safer than being reductionist.

I also think it's dangerous to be mystical unless you see it as metaphorical in which case it's a lot safer than being reductionist.

Thursday, 22 September 2011

I have to admit it.

I was a hipster at age 7. 1984. The year that brought the world not Big Brother but Little (Peter) Pan; Michael 'Thriller' Jackson. India tended to lag behind Western pop culture by a few years at the time. Actually for more than a few years and not just at that time, but I grow dilatory. Michael Jackson cut through; all the big pop spectacles did, I now realise: Madonna, Live Aid, Sam Fox pin-ups and Bruce Springsteen bellowing 'Born In The USA' on an Indian stage in the 80s. We didn't have Pepsi and Coke but Michael Jackson cassettes and all sorts of bootleg merchandise started filtering through: dance moves discussed eagerly by teens after attending Sunday school in the Mennonite church next door, the kids in the street behind mine added a small alien element to their usual round of kirket heroes and Hindi film matinee idols, classmates humming Jackson tunes etc.

Even then I was convinced enough of the superiority of my own tastes (Beatles, Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel, Stones, all picked up from my parents' collections) and the utter despicability of anything that was so popular that people who didn't know from good music, who didn't care about what had come before, could latch on to this new sound and claim it and let it claim them.

I haven't grown up. I'm still that elitist 7-year old. I distrust the popular, look away from the spectacle, criticise the widely-acclaimed. A.R. Rahman the Mozart of Madras? Clearly you have never heard Mozart or been to Madras. And this (not at all) new rock that calls itself 'indie' and is perhaps not the mainstream but is certainly a mainstream fills me with instinctual contempt for all those whispy voices, those jangly guitars, mannerism as method, quirk as quorum. I listen to so many different kinds of music but I make a point to identify as a metalhead just to piss off the hipsters. I've become so hip I look down not on the mass audience but on other niche audiences.

Even then I was convinced enough of the superiority of my own tastes (Beatles, Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel, Stones, all picked up from my parents' collections) and the utter despicability of anything that was so popular that people who didn't know from good music, who didn't care about what had come before, could latch on to this new sound and claim it and let it claim them.

I haven't grown up. I'm still that elitist 7-year old. I distrust the popular, look away from the spectacle, criticise the widely-acclaimed. A.R. Rahman the Mozart of Madras? Clearly you have never heard Mozart or been to Madras. And this (not at all) new rock that calls itself 'indie' and is perhaps not the mainstream but is certainly a mainstream fills me with instinctual contempt for all those whispy voices, those jangly guitars, mannerism as method, quirk as quorum. I listen to so many different kinds of music but I make a point to identify as a metalhead just to piss off the hipsters. I've become so hip I look down not on the mass audience but on other niche audiences.

Sunday, 18 September 2011

cud

The streets the lower jaw

Of a huge mouth

Gap-toothed, riddled with cavities

And unlikely, impractical and hideous

Caps and dentures

Of varying ages.

The upper jaw

Is already clamped shut.

The city chews you.

Of a huge mouth

Gap-toothed, riddled with cavities

And unlikely, impractical and hideous

Caps and dentures

Of varying ages.

The upper jaw

Is already clamped shut.

The city chews you.

Labels:

fuck you im a poet

Monday, 5 September 2011

FADE TO BLONDE BY MAX PHILLIPS

Whoever Max Phillips is* (I used to be one of those reviewers who did a lot of research, but that just meant my reviews wound up being regurgitated facts and subconscious plagiarism so now I make like Jack Spader and wait for a review to be dictated to me. By ghosts) he does a damned fine job of writing a vintage piece of noir, set in the seamy margins of the film business sometime in the 1950s, as far as I can tell from internal references. He goes straight for Chandler/Hammett territory and for the most part delivers a convincing period piece, right down to the somewhat rambling, episodic middle-acts that both the aforementioned masters often delivered, moving their sleuths from one seedy venue to another explosive confrontation to get the pieces in place for the final blow. Still, there are times when it's clear from certain mannerisms in the dialogue (especially the ploy of making 70% of a sentence? A question) that the writer has lived through the 2000s.

That's a minor complaint, because Phillips certainly delivers on most other fronts with a variety of colourful character, all sorts of sordid set-pieces and bursts of frantic action. There's a dame, and she's bad news for everyone around, especially herself. There's a hood, but we don't know everything about him until it's almost too late. There's a patsy, but the dame and the hood don't have his full measure. Various gangsters, crooks, lowlifes, minor functionaries, film world nobodies & used-to-be-somebodies and so forth prowl around the edges of the narrative darting in for quick bits of snappy dialogue and plot advancement. If anything, this novel is a bit too crowded for its 220 or so pages.

A bigger complaint is that the protagonist just doesn't add up. A failed screen writer and sometime-boxer, sometime bit-actor, he lived through some frightening moments in the second world war, but he's also well-read in a hard-bitten sort of way (he likes Chekhov and Stephen Crane, Hemingway tires him out). None of this really explains why he's such a fucking psycho. When anyone else would have been happy to get in a couple of solid punches and wind their opponent long enough to make a clean getaway, Corson will go for the jugular, every single time. Excessive violence is his only action mode and even in the tough circles he moves around in, he is known to be a bit of a wild card. Only, we're never given sufficient reasons why this is so.

So there you have it. Lots of good one-liners, a suitably sordid plot and a pretty good stab at old-fashioned noir entertainment through degradation even if there is an attempt to let a little sunshine through at the every end. Not something that I'll include in my list of all-time favourites, but by no means a bad way to spend your time and money.

*So I did my research afterwards, and he's one of the people running Hard Case crime. A bit cheeky to make one of his own books the second in the series, but at least it's obvious that this is an operation run by people who know a thing or two about their chosen area of operation. Also he gets huge points from me for this interview answer:

GM: Ray Corson, Mike Hammer, Phillip Marlowe and Jeff Markham are in a bar and get into a drunken brawl. Who’s going to win?

MP: Jules Maigret glares at them over his beer and they all slink out in shame.

That's a minor complaint, because Phillips certainly delivers on most other fronts with a variety of colourful character, all sorts of sordid set-pieces and bursts of frantic action. There's a dame, and she's bad news for everyone around, especially herself. There's a hood, but we don't know everything about him until it's almost too late. There's a patsy, but the dame and the hood don't have his full measure. Various gangsters, crooks, lowlifes, minor functionaries, film world nobodies & used-to-be-somebodies and so forth prowl around the edges of the narrative darting in for quick bits of snappy dialogue and plot advancement. If anything, this novel is a bit too crowded for its 220 or so pages.

A bigger complaint is that the protagonist just doesn't add up. A failed screen writer and sometime-boxer, sometime bit-actor, he lived through some frightening moments in the second world war, but he's also well-read in a hard-bitten sort of way (he likes Chekhov and Stephen Crane, Hemingway tires him out). None of this really explains why he's such a fucking psycho. When anyone else would have been happy to get in a couple of solid punches and wind their opponent long enough to make a clean getaway, Corson will go for the jugular, every single time. Excessive violence is his only action mode and even in the tough circles he moves around in, he is known to be a bit of a wild card. Only, we're never given sufficient reasons why this is so.

So there you have it. Lots of good one-liners, a suitably sordid plot and a pretty good stab at old-fashioned noir entertainment through degradation even if there is an attempt to let a little sunshine through at the every end. Not something that I'll include in my list of all-time favourites, but by no means a bad way to spend your time and money.

*So I did my research afterwards, and he's one of the people running Hard Case crime. A bit cheeky to make one of his own books the second in the series, but at least it's obvious that this is an operation run by people who know a thing or two about their chosen area of operation. Also he gets huge points from me for this interview answer:

GM: Ray Corson, Mike Hammer, Phillip Marlowe and Jeff Markham are in a bar and get into a drunken brawl. Who’s going to win?

MP: Jules Maigret glares at them over his beer and they all slink out in shame.

Monday, 29 August 2011

FALL INTO TIME BY DOUGLAS LAIN

I'd actually read two of these stories when they first appeared in online magazines. This is Lain's second book-form publication, the first was his debut short story collection, Last Week's Apocalypse. Lain's stories exist somewhere on the intersection of PKD, Kafka and a William Gibson who is more engaged with personal spaces and ideological possibilities than that funky data dance. I consider him one of the most exciting and intriguing writers I've encountered in the contemporary SF field, albeit one who does not press the buttons the bulk of genre fans expect their writers to. I'll try and weigh in with a more detailed version of this review sometime when it isn't a saturday evening and I don't have a bottle of excellent whiskey at hand.

*time elapses*

Right, it's Monday morning. You know, I used to spread drinking through the week, but lately I seem to get it all done in a few hours on Saturday evenings. Improved time management skills, I suppose.

I'd like to add a story-by-story review of this book which is easy because it only contains 4 stories.

The Last Apollo Mission: Lain parlays moon landing fraud theories and post-9/11 conspiracy paranoia into a story about a failed (or is she?) writer's intersection with a top-secret Kubrick project and the very bizarre aftermath. When you accept that everything's part of a conspiracy theory, what happens when conspiracies collide?

Resurfacing Billy: In a near-future where toxic waste is being dumped in public spaces and seeping out everywhere, a man tries to invent a miracle substance that will seal the garbage in for good. At the same time, the private franchise school he sends his son Billy to is attempting to find ways to curb Billy's supposedly anti-social streak, and is willing to use means that extend all the way up to lobotomy. Something about our increasingly counter-productive problem-solving strategies as a species, I think. The most emotionally poignant story in this set.

Alien Invasion/Coffee Cup Story: Dozens of SF fans love to hate this parody of the slice-of-life epiphany short story, spliced with an infuriatingly static alien invasion scenario. We expect too much from things, whether they're drunken conversations in bars or gleaming spacecraft hanging in the sky.

Chomsky And The Time Box: In a recent essay on Zizek, Lain says 'The only thing to expect from Zizek is that he challenges us to think and create new modes of Praxis. Not that we should stay at Zizek's level of political intervention, but rather that we should brutally test his ideas and criticize him so that we can discover to what degree the impossible is possible'. I think this story is of a piece with that sentiment, it's partly a commentary on our need to find gurus, using two such disparate figures as Chomsky and mushroom-mystic Terence McKenna to convey this point. It's also a hilarious, frustrating take on the history-changing time travel trope and there are one or two things here about our consumerist obsession with gadgets and gratification.

I may have made these stories seem like dry exercises in making points; in fact each of them has a richly textured narrative and is often downright hilarious. I'm a steadily-lapsing SF fan who finds that most current strands of the genre have very little to do with his own futuristic or literary interests. Lain is the rare writer who addresses my increasing need to read SF that engages with the currents that are really shaping our world in a mode that owes more to the 70s New Wave, for instance, than to Crichton-envy. Well done!

*time elapses*

Right, it's Monday morning. You know, I used to spread drinking through the week, but lately I seem to get it all done in a few hours on Saturday evenings. Improved time management skills, I suppose.

I'd like to add a story-by-story review of this book which is easy because it only contains 4 stories.

The Last Apollo Mission: Lain parlays moon landing fraud theories and post-9/11 conspiracy paranoia into a story about a failed (or is she?) writer's intersection with a top-secret Kubrick project and the very bizarre aftermath. When you accept that everything's part of a conspiracy theory, what happens when conspiracies collide?

Resurfacing Billy: In a near-future where toxic waste is being dumped in public spaces and seeping out everywhere, a man tries to invent a miracle substance that will seal the garbage in for good. At the same time, the private franchise school he sends his son Billy to is attempting to find ways to curb Billy's supposedly anti-social streak, and is willing to use means that extend all the way up to lobotomy. Something about our increasingly counter-productive problem-solving strategies as a species, I think. The most emotionally poignant story in this set.

Alien Invasion/Coffee Cup Story: Dozens of SF fans love to hate this parody of the slice-of-life epiphany short story, spliced with an infuriatingly static alien invasion scenario. We expect too much from things, whether they're drunken conversations in bars or gleaming spacecraft hanging in the sky.

Chomsky And The Time Box: In a recent essay on Zizek, Lain says 'The only thing to expect from Zizek is that he challenges us to think and create new modes of Praxis. Not that we should stay at Zizek's level of political intervention, but rather that we should brutally test his ideas and criticize him so that we can discover to what degree the impossible is possible'. I think this story is of a piece with that sentiment, it's partly a commentary on our need to find gurus, using two such disparate figures as Chomsky and mushroom-mystic Terence McKenna to convey this point. It's also a hilarious, frustrating take on the history-changing time travel trope and there are one or two things here about our consumerist obsession with gadgets and gratification.

I may have made these stories seem like dry exercises in making points; in fact each of them has a richly textured narrative and is often downright hilarious. I'm a steadily-lapsing SF fan who finds that most current strands of the genre have very little to do with his own futuristic or literary interests. Lain is the rare writer who addresses my increasing need to read SF that engages with the currents that are really shaping our world in a mode that owes more to the 70s New Wave, for instance, than to Crichton-envy. Well done!

Friday, 19 August 2011

romans durs, anyone?

Do you know any fans of Simenon's non-Maigret books? I'd like to put together a site/community dedicated to these books as a counterpart to the excellent Maigret site at trussel.com/f_maig

Wednesday, 17 August 2011

killing the alien

Mrs. Radcliffe sought to tame the wild Gothic, tether it to reason and human nature. Leaving a back door for the restitution of strangeness and transgression depending on your paradigm of reason, human nature and reality.

Messers Burton & Gaiman have, cumulatively (they both have individual works or sequences that do not do this; the pop-cultural end-result is what I am getting at here) done much more damage to the power of such imagery to evoke the dark and numinous than Radcliffe or Reeve ever did. Through them, the trappings of Gothic are no longer barbaric, menacing or strange; Death is just a pale girl in black who knows all about you and loves you.

The work of transforming the Gothic into the psychological novel, the novel of manners, the detective novel and the science fiction novel was creative. The work of transforming the dark and alien into the safe, familiar and domestic is far more pernicious; instead of true disruption we are led to a universe where everything mirrors everything else.

Messers Burton & Gaiman have, cumulatively (they both have individual works or sequences that do not do this; the pop-cultural end-result is what I am getting at here) done much more damage to the power of such imagery to evoke the dark and numinous than Radcliffe or Reeve ever did. Through them, the trappings of Gothic are no longer barbaric, menacing or strange; Death is just a pale girl in black who knows all about you and loves you.

The work of transforming the Gothic into the psychological novel, the novel of manners, the detective novel and the science fiction novel was creative. The work of transforming the dark and alien into the safe, familiar and domestic is far more pernicious; instead of true disruption we are led to a universe where everything mirrors everything else.

Sunday, 14 August 2011

Wednesday, 10 August 2011

'Where is the writer,' he began, 'who is unstained by any habits of the human, who would be the ideal of everything alien to living, and whose own eccentricity, in its darkest phase, would turn in on itself to form increasingly more complex patterns of strangeness? Where is the writer who has remained his entire life in some remote dream that he inhabited from his day of birth, if not long before?'

- Thomas Ligotti, 'The Journal Of J.P. Drapeau '

Tuesday, 9 August 2011

a political tout

China Mieville, responding to a reader who asked if he would ever be willing to write something that did not 'tout' his 'Liberal politics':

From this thread on goodreads: http://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/566606-ask-china-mi-ville?format=html&page=1

The way I see the world is, among other things but very importantly, a political one, and I write fiction from where I see the world. Therefore, it’s no surprise that the concerns, interests, textures and tractions that inform the fiction are, to various degrees recognizably, related to my politics. Just as they are with many other writers, of all kinds of varying positions, for whom politics are important.

So when you ask if I’m ‘willing to write anything that doesn’t tout’ my own position, how I have to interpret that is ‘Are you willing to write a book that is not written from a position of seeing the world the way you see the world?’ To which, the answer, of course, has to be No. How could I possibly do so? I don’t want to do so, either, even if I could, which I cannot. The things you say you like in the books come from the same place of which the politics are an inextricable component. I don’t say they’re coterminous – but they are inextricable in my head, and I don’t want to extricate them.

From this thread on goodreads: http://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/566606-ask-china-mi-ville?format=html&page=1

Saturday, 6 August 2011

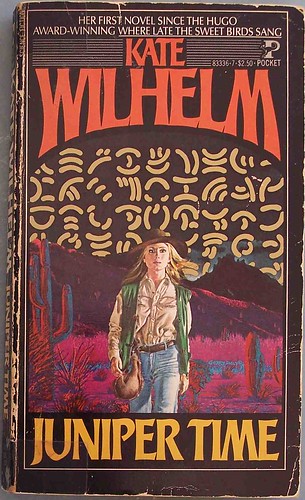

JUNIPER TIME BY KATE WILHELM

Mostly very good, even if, purely as extrapolation, a lot of plot elements haven't held up. A very canny and thoughtful derailment of a carefully built-up first contact motif set against a near future world where international conflict and ecological crisis prevail.

Where the novel failed for me, right at the eleventh hour, was in the excessively expository manner in which the conflicts and resolutions of the last 20 pages are played out, all tell and no show. Wilhelm has points to make about human motivation, the dehumanising nature of obsession, our pathetic management of the environment, our addiction to one-upmanship and our counter-productive attachment to seeing things as binaries. She also creates at least one fascinating central character; but he is not sympathetic, and one sympathetic character; but she is too good to be true. The rest of the characters are like stock figures in a passion play. Despite which there is some very beautiful writing that displays an admirable sense of place and grasp of metaphor.

A wise book, but not enough of a novel. By way of contrast, see Ursula Le Guin's The Lathe Of Heaven, which exemplifies why John Clute describes Le Guin as a 'wise teller of tales'.

Where the novel failed for me, right at the eleventh hour, was in the excessively expository manner in which the conflicts and resolutions of the last 20 pages are played out, all tell and no show. Wilhelm has points to make about human motivation, the dehumanising nature of obsession, our pathetic management of the environment, our addiction to one-upmanship and our counter-productive attachment to seeing things as binaries. She also creates at least one fascinating central character; but he is not sympathetic, and one sympathetic character; but she is too good to be true. The rest of the characters are like stock figures in a passion play. Despite which there is some very beautiful writing that displays an admirable sense of place and grasp of metaphor.

A wise book, but not enough of a novel. By way of contrast, see Ursula Le Guin's The Lathe Of Heaven, which exemplifies why John Clute describes Le Guin as a 'wise teller of tales'.

Labels:

book review,

juniper time,

kate wilhelm,

science fiction

Friday, 5 August 2011

THE SKULL OF TRUTH BY BRUCE COVILLE

Good children's books deserve to be read by adults as well. If it's really good, the story will appeal to readers of any age. If it's downright excellent, it can re-awaken the child within for the space it takes to read the book. Maybe it's because I went to a pre-school run on the system of Maria Montessori, whose watchword was 'follow the child', but I can't help but see that as a beneficial exercise.

Bruce Coville is a prolific American writer of fiction for children whom I first discovered in my 20s, with the 'My Teacher Is An Alien' books. I was impressed by how real and believable his characters are, children, grown-ups and aliens and how well his imagination conjures up situations and settings that invoke a sense of wonder. I also noted how he handles larger messages and themes in a way that's not preachy or intrusive and is alive to the many sides of any given issue. Most of all, I was taken by Coville's obvious joy in the art of storytelling.

In this book, Coville tackles one of the big issues any fictioneer has to grapple with at some point: truth. When Charles Egglestone stumbles into a mysterious shop and winds up shoplifting a talking skull, he finds that the skull's magical powers have made it impossible for him to lie anymore. At first, disaster follows, because the truth is not always the convenient or even the right thing to blurt out. Gradually, he gains a deeper, richer sense of what truth is all about, how it can be found both in fact and fiction and how it can be used for good, although it is in itself morally neutral. I was particularly glad that Coville keeps that last point very clearly in sight. Truthfulness isn't a magic key to virtue - it's still up to us to keep our eyes open and work out the ethics of everything we do. I can think of vast tomes written for a putatively grown-up audience that miss this point.

That exposition of the book's themes probably sounds dry. But this book isn't. It's hilarious, poignant and inventive, and manages to invoke a character from Big Bill Shakespeare's plays - see if you can guess which one - and give him a back- and front-story, if I can put it that way, which is as resonant and memorable as anything from the Bard's plays. I get a real kick out of a piece of fiction that can engage with one of the classics and emerge enriched rather than simply bested by the experience, and the former is certainly the case here. (Neil Gaiman has done this sort of thing well at points in his career - Sandman for instance - and not so well at other points - the Beowulf film). If I had a child between the ages of 7 and 11 at my disposal, I would entreat him or her to read this book. But since I don't, I'm just as happy to have had the chance to read it myself.

Bruce Coville is a prolific American writer of fiction for children whom I first discovered in my 20s, with the 'My Teacher Is An Alien' books. I was impressed by how real and believable his characters are, children, grown-ups and aliens and how well his imagination conjures up situations and settings that invoke a sense of wonder. I also noted how he handles larger messages and themes in a way that's not preachy or intrusive and is alive to the many sides of any given issue. Most of all, I was taken by Coville's obvious joy in the art of storytelling.

In this book, Coville tackles one of the big issues any fictioneer has to grapple with at some point: truth. When Charles Egglestone stumbles into a mysterious shop and winds up shoplifting a talking skull, he finds that the skull's magical powers have made it impossible for him to lie anymore. At first, disaster follows, because the truth is not always the convenient or even the right thing to blurt out. Gradually, he gains a deeper, richer sense of what truth is all about, how it can be found both in fact and fiction and how it can be used for good, although it is in itself morally neutral. I was particularly glad that Coville keeps that last point very clearly in sight. Truthfulness isn't a magic key to virtue - it's still up to us to keep our eyes open and work out the ethics of everything we do. I can think of vast tomes written for a putatively grown-up audience that miss this point.

That exposition of the book's themes probably sounds dry. But this book isn't. It's hilarious, poignant and inventive, and manages to invoke a character from Big Bill Shakespeare's plays - see if you can guess which one - and give him a back- and front-story, if I can put it that way, which is as resonant and memorable as anything from the Bard's plays. I get a real kick out of a piece of fiction that can engage with one of the classics and emerge enriched rather than simply bested by the experience, and the former is certainly the case here. (Neil Gaiman has done this sort of thing well at points in his career - Sandman for instance - and not so well at other points - the Beowulf film). If I had a child between the ages of 7 and 11 at my disposal, I would entreat him or her to read this book. But since I don't, I'm just as happy to have had the chance to read it myself.

Labels:

book review,

childrens fiction

Saturday, 30 July 2011

Wednesday, 27 July 2011

blocked

story wavers

words shimmer

i reach but cannot grip

sense remains

sense prevails

i give up

words go back in single file

along the bleak marches

all the way back into

that dark country

of the unimagined

words shimmer

i reach but cannot grip

sense remains

sense prevails

i give up

words go back in single file

along the bleak marches

all the way back into

that dark country

of the unimagined

Labels:

fuck you i'm a poet

Friday, 24 June 2011

Saturday, 18 June 2011

Five Equally Plausible Rules of Good Writing

Another reply to another post by Ian Sales:

- Leave enough room in your prose for the ambiguity that recruits the reader's imagination as a willing collaborator.

- Sometimes, it's best if you let the reader map out that last ramification of the ideas in the story.

- Leave enough room in the plot for the reader to have something to ponder over later.

- Get the details right (and that means research).

- The resolution needs to be a natural consequence of your intentions in writing the story.

Thursday, 16 June 2011

All-Authoress July

I haven't really been following Ian Sales' SF Mistressworks project, because I haven't really been keeping up with the SF blogsphere but he makes some good points here.

He plans to only read books by women in July and considering the fact that my own reading is dominated by male authors I feel I could definitely gain by following suit. I read about 4 to 5 books a month so here is a list of authors by whom I have one or more unread books that could make it into next month's reading list:

Jessica Amanda Salmonson

Jeanette Winterson

Sarah Hall

Angela Carter

Jane Yolen

CJ Cherryh

Minette Walters

That's by no means a comprehensive list, but it covers several books that I was planning to read soon anyway. In every case I've already read something by this author, so maybe I should also add a couple of new discoveries to the mix, but here's the shortlist of authors I will be choosing from.

He plans to only read books by women in July and considering the fact that my own reading is dominated by male authors I feel I could definitely gain by following suit. I read about 4 to 5 books a month so here is a list of authors by whom I have one or more unread books that could make it into next month's reading list:

Jessica Amanda Salmonson

Jeanette Winterson

Sarah Hall

Angela Carter

Jane Yolen

CJ Cherryh

Minette Walters

That's by no means a comprehensive list, but it covers several books that I was planning to read soon anyway. In every case I've already read something by this author, so maybe I should also add a couple of new discoveries to the mix, but here's the shortlist of authors I will be choosing from.

The Very Slow Time Machine by Ian Watson

This book is full of the sort of mind-bending ideas and narrative experiments that I like best in my science fiction - Watson is very much writing in a British SF tradition, that of Brian Aldiss and JG Ballard I'd say, but his vision is his own. Much as I loved the caliber of Watson's conceits (a mind-meld with an entity within a black hole whose idea of reality is an inversion of our own, a visit to an Earth where impermeable barriers divide various regions along meridional lines, a sojourn among aliens who extend further in time than we do - and what exactly that could mean - and more) and his formal freedom (several of these stories do not deliver conventional narratives but almost fragmentary vignettes), I disliked aspects of his treatment of gender and race. Most female characters are sexualised and people are often characterised a little too strongly according to race or ethnicity. Still a definite classic for all that, and easily goes into my list of favourite SF short story collections. Will be looking out for the new one Ian Whates is publishing.

Tuesday, 14 June 2011

Reading the scathing user-submitted reviews of Vinyan on IMDB, all written by self-proclaimed horror fans, I suspect that there is something fundamentally different by what I mean when I identify as a horror fan (and sometimes writer) and what these people are talking about.

Vinyan doesn't deal in physical evisceration or torture as its primary currency; it holds back on the gore until circumstances dictate that it cannot be avoided any longer; it grants meaning and narrative weight to the act of gutting a human being, a weight that films like the Saw franchise fail to convey.

Instead of serving as a sort of Sadeopedia, it deals with terrible consequences of loss and obsession, following a couple who are perhaps trying to expiate their own sense of guilt over a lost child, as they journey to the heart of their own particular darkness.

There is a supernatural element: a suggestion that a vinyan, the troubled spirit of one who dies a bad death, may exist even before such a death. Are the couple in this film being drawn into their own darkest hours by the spirit of a lost child or by some sort of unleashed anguish from their own dark destinies?

The supernatural suggestion is weighed against an evocative depiction of the unsettling, perspective-upsetting consequences of strong, perhaps pathological, emotion.

Everyone here has survived a terrible catastrophe; at least, they are all still alive. But it is unclear if their sanity and humanity has survived.

Seeds are sown, a terrible harvest is reaped. We are left to piece together whether it was human nature or the spirit world, or both, that intervened.

I think it's a horror film, using the term 'horror' as a shorthand for any narrative that seeks to unsettle us by exploring the darker potential inherent in things natural and supernatural. I also think it's a pretty good horror film.

Vinyan doesn't deal in physical evisceration or torture as its primary currency; it holds back on the gore until circumstances dictate that it cannot be avoided any longer; it grants meaning and narrative weight to the act of gutting a human being, a weight that films like the Saw franchise fail to convey.

Instead of serving as a sort of Sadeopedia, it deals with terrible consequences of loss and obsession, following a couple who are perhaps trying to expiate their own sense of guilt over a lost child, as they journey to the heart of their own particular darkness.

There is a supernatural element: a suggestion that a vinyan, the troubled spirit of one who dies a bad death, may exist even before such a death. Are the couple in this film being drawn into their own darkest hours by the spirit of a lost child or by some sort of unleashed anguish from their own dark destinies?

The supernatural suggestion is weighed against an evocative depiction of the unsettling, perspective-upsetting consequences of strong, perhaps pathological, emotion.

Everyone here has survived a terrible catastrophe; at least, they are all still alive. But it is unclear if their sanity and humanity has survived.

Seeds are sown, a terrible harvest is reaped. We are left to piece together whether it was human nature or the spirit world, or both, that intervened.

I think it's a horror film, using the term 'horror' as a shorthand for any narrative that seeks to unsettle us by exploring the darker potential inherent in things natural and supernatural. I also think it's a pretty good horror film.

Thursday, 9 June 2011

Wednesday, 25 May 2011

Dylanish

In a recent blog entry, M. John Harrison lists what one assumes are his favourite Dylan songs. Here's a YouTube playlist featuring all of them in cover versions for reasons that will forever alienate hardcore Dylan fans. Cheers.

Monday, 23 May 2011

Ticket Of Leave (a.k.a. The Widow) by Georges Simenon

'It was odd: there were forty passengers, and only one of them, the widow Couderc, looked at the man any differently than you would have looked at just anybody.The rest were placid and quiet, as it might be cows in a meadow watching a wolf browsing in their midst without the least astonishment.'

'Twice, and twice only, in the whole of his life, had he known this innocent peace, once when he'd been ill and had ceased to consider school a reality; then again here, this very morning, as he strode towards the village and waited with the gossips behind the butcher's van...'

'Twice, and twice only, in the whole of his life, had he known this innocent peace, once when he'd been ill and had ceased to consider school a reality; then again here, this very morning, as he strode towards the village and waited with the gossips behind the butcher's van...'

Wednesday, 18 May 2011

Writing news

My story 'Dancer of the Dying' has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Cthulhu: Nightmare Cities, an anthology of Lovecraftian stories. It's Lovecraftian in the sense that it takes cues from 'The Music Of Erich Zann' and 'The Festival' but the nightmare city in question is, of course, Bangalore.

Thursday, 12 May 2011

Wednesday, 11 May 2011

survive

'Flight is many things. Something clean and swift, like a bird skimming across the sky. Or something filthy and crawling; a series of crablike movements through figurative and literal slime, a process of creeping ahead, jumping sideways, running backward.

It is sleeping in fields and river bottoms. It is bellying for miles along an irrigation ditch. It is back roads, spur railroad lines, the tailgate of a wildcat truck, a stolen car and a dead couple in lovers' lane. It is food pilfered from freight cars, garments taken from clotheslines; robbery and murder, sweat and blood. The complex made simple by the alchemy of necessity.'

'...that thing that's taken refuge there in that zinc bucket, without a wife, a career, a conapt, or money or the possibility of encountering any of these, still persists. For reasons unknown to me its stake in existence is greater than mine.'

Monday, 9 May 2011

'a funny world, kid'

'We're living in a funny world kid, a peculiar civilization. The police are playing crooks in it, and the crooks are doing police duty. The politicians are preachers, and the preachers are politicians. The tax collectors collect for themselves. The Bad People want us to have more dough, and the good people are fighting to keep it from us. It's not good for us, know what I mean? If we had all we wanted to eat, we'd eat too much. We'd have inflation in the toilet paper industry. That's the way I understand it. That's about the size of some of the arguments I've heard.'

- Jim Thompson, 'The Killer Inside Me'

- Jim Thompson, 'The Killer Inside Me'

Thursday, 28 April 2011

The Whole Wide World (1996)

Robert E Howard was long my least favourite of the Big Three weird writers, as a person. While Lovecraft shared his racism, he was also a reclusive, cat-loving, atheistic ice-cream eater, all qualities I can relate to. Clark Ashton Smith always seemed the most fully-rounded personality of the three and the one with the most liberal, sensible views on life. Howard came across as a racist social misfit who wrote the stories he did as a sort of wish-fulfillment for the life of machismo that he longed for but was born too late to have. I've actually read a bit about his life, including extensive excerpts from Novalyne Price's memoirs, but this movie finally put it all in perspective for me. It doesn't soft-pedal anything except the racism, which is completely side-stepped. Howard is shown as a dreamer, someone whose stories were as much the product of a powerful imagination as they were of a deeply unfulfilled personality. His relationship with his mother is there in all its obsessive dimension, as is his penchant for ungainly macho posturing. Despite all this, we see a sensitive, intelligent man who was driven driven: both by personal demons, demons that eventually triumphed, and by something that conforms more to the classical concept of the genius; a sort of tutelary spirit whispering wondrous yarns into his inner ear. The movie also bypasses the question of poverty - the Howards' finances were a major concern for REH and his depression over delayed payments for his stories contributed in large measure to his depression. Still, this was a wonderful experience and a take on REH that feels right in the context of what I can conclude about the man from his fiction.You don't need to like the authors you read, but I think I have a better, more sympathetic sense of Howard the man today.

Friday, 22 April 2011

Presenting a rough cut of a song by my new side-project, Djinn & Miskatonic: Flight Of Sand. The final version will include distortion on the bass (my battery died just before this recording) and vocals! And fewer mistakes!!

Thursday, 21 April 2011

Maigret's Pickpocket by Georges Simenon

A reviewer on goodreads.com described this book as comfort food, and noted the civilized way in which Maigret goes about solving his mystery. That makes it seem as if this is something on the lines of an Agatha Christie novel, which strikes me as a very misleading notion. However, it also illuminates a difference between Simenon's Franco-Belgian noir and the American version: there's far less violence in Simenon's Maigret novels. Maigret doesn't go around getting into brawls, ambushes and gunfights the way Marlow or the Continental Op do.

You could almost describe the set-up as a police procedural; except that Maigret's procedure is anything but. He generally approaches a case obliquely, famously drawing no conclusions and forming no theories, almost sleepwalking through routine interrogations and noting each new piece of data from the experts with an almost distracted air. He takes time out for snacks, glasses of beer or wine, little domestic interludes with his wife. His deductions only come in at the very end, once he has completely immersed himself in the mystery to the point of outward stasis. He is informed by a deep, not un-compassionate sense of human frailty and a professional policeman's knowledge of all the twisted, brutal and pathetic forms that frailty can take; it's a sensitive clinician's approach, a description which can be applied to Simenon's own in these novels as well as his non-Maigret works. In the process we are brought face-to-face with some of the darkest currents of human nature, with acts of betrayal and desperation that are more shocking for being uncovered in such a seemingly matter-of-fact way. It isn't a superior approach to that of Chandler/Hammett , but an equally effective one, and one that has more in common with their work than that of those whom I'd generally describe as writers of cozy mysteries.

This novel is no exception; it is superbly constructed, with Maigret's wallet being pick-pocketed on a bus - only to be returned intact with a note requesting him to meet the pickpocket. The fellow turns out to be a young aspiring scriptwriter who lives alone with his wife in a flat. His wife has been dead for a few days, shot in the head. The man insists he is innocent and turns to Maigret for help. What follows is a descent into a specific microcosm - the world of somewhat shifty financiers, wannabe stars and creative hacks of various kinds who exist at the peripheries of the film world, looking out for their big break. Outwardly, Maigret is having a pleasant time of it, sitting and eavesdropping on his suspects in a cozy restaurant with superb food, sharing fine beer with one suspect and so on.

But I am convinced that any reader with a little discernment will notice the darker currents running beneath this calm surface, the little side-lights into the various characters' own individual hells, the tiny acts of betrayal and desperation, calculation and surmise that make up their daily lives, and finally the revelation of the crime itself, domestic certainly, but not cozy by any means. Even more significant than Maigret's identification of the culprit is his insight in the last page - asked if the culprit should face the courts or be treated as a psychiatric case, Maigret suggests the courts - not because he is convinced of the murderer's mental soundness so much as because he knows that that is where the person in question will be able to play out the sort of role they would be most comfortable with. That's a subtle point, one that neither justifies nor condemns but merely displays the stark insight that sets the Maigret novels apart.

You could almost describe the set-up as a police procedural; except that Maigret's procedure is anything but. He generally approaches a case obliquely, famously drawing no conclusions and forming no theories, almost sleepwalking through routine interrogations and noting each new piece of data from the experts with an almost distracted air. He takes time out for snacks, glasses of beer or wine, little domestic interludes with his wife. His deductions only come in at the very end, once he has completely immersed himself in the mystery to the point of outward stasis. He is informed by a deep, not un-compassionate sense of human frailty and a professional policeman's knowledge of all the twisted, brutal and pathetic forms that frailty can take; it's a sensitive clinician's approach, a description which can be applied to Simenon's own in these novels as well as his non-Maigret works. In the process we are brought face-to-face with some of the darkest currents of human nature, with acts of betrayal and desperation that are more shocking for being uncovered in such a seemingly matter-of-fact way. It isn't a superior approach to that of Chandler/Hammett , but an equally effective one, and one that has more in common with their work than that of those whom I'd generally describe as writers of cozy mysteries.

This novel is no exception; it is superbly constructed, with Maigret's wallet being pick-pocketed on a bus - only to be returned intact with a note requesting him to meet the pickpocket. The fellow turns out to be a young aspiring scriptwriter who lives alone with his wife in a flat. His wife has been dead for a few days, shot in the head. The man insists he is innocent and turns to Maigret for help. What follows is a descent into a specific microcosm - the world of somewhat shifty financiers, wannabe stars and creative hacks of various kinds who exist at the peripheries of the film world, looking out for their big break. Outwardly, Maigret is having a pleasant time of it, sitting and eavesdropping on his suspects in a cozy restaurant with superb food, sharing fine beer with one suspect and so on.

But I am convinced that any reader with a little discernment will notice the darker currents running beneath this calm surface, the little side-lights into the various characters' own individual hells, the tiny acts of betrayal and desperation, calculation and surmise that make up their daily lives, and finally the revelation of the crime itself, domestic certainly, but not cozy by any means. Even more significant than Maigret's identification of the culprit is his insight in the last page - asked if the culprit should face the courts or be treated as a psychiatric case, Maigret suggests the courts - not because he is convinced of the murderer's mental soundness so much as because he knows that that is where the person in question will be able to play out the sort of role they would be most comfortable with. That's a subtle point, one that neither justifies nor condemns but merely displays the stark insight that sets the Maigret novels apart.

Tuesday, 12 April 2011

my recent forays into the world of trash horror

Spawn by Shaun Hutson

Over the last few years, I have been reading some of the finest horror literature in the world, delving deep into the British ghost story masters James and Le Fanu, the spritualist-horror masterpieces of Machen and Blackwood, the darker American visions of Bierce, Chambers and that dark prince of the macabre, Poe, the early 20th-century efflorescence helmed by talents like Lovecraft, Smith and Howard and of course the current masters of the form such as Ligotti and Campbell as well as emerging giants like Barron and Pugmire.

And now I've read Shaun Hutson.

This isn't the worst thing ever - writers like Richard Laymon and the authors of a hundred disposable splatter paperbacks from the 80s boom were as bad and often worse - but it's not good by any means. The writing is amateurish and in need of editing, the plot is a mish-mash of cliches and poor taste, the characters are cardboard cut-outs and there's no real moment of dark epiphany, just a series of rather lowbrow gross-outs that culminate in the usual predictable twist ending.

For all that, I'm giving this a two-star rating simply because of its honesty - Hutson clearly set out to write exactly the kind of novel that he wound up writing. It's trash, but at least it's honest trash and nothing - the title, the blurb, the cover art or what you can glean by scanning the first few pages in a bookstore - pretends otherwise.

The House Of Doors by Brian Lumley

Lovecraftian robes, MacLeanian heart.

I'd vaguely heard of Lumley and his never-ending Necroscope series as well as his Lovecraftian fiction. What I'd heard of the former didn't exactly have me rushing to check out the latter, but I decided to finally sample something by him and this novel seemed like a good place to start as I wanted something outside of the Necroscope series to start with.

The novel is billed as horror, but really, it's closer to science fiction, and even closer to a plan and simple action thriller. Lumley certainly has a powerful if raw imagination; much of the rest is simply undercooked or half-baked. The appearance of a weird castle in a small Scottish town is certainly a promising set-up, and when we finally enter this strange place some of the imagery Lumley spins is suitably awesome, if couched in somewhat less than deathless prose. But the story begins to bog down with its characters; the hero is somewhat interesting in that he possesses an unusual ability to enter into a sort of empathetic rapport that lets him fathom how anything mechanical works; he is also dying of a fatal disease. Beyond that, however, he remains as much of a cipher as the remaining stock characters; a heavy-handed, arrogant politician, a tough secret agent with bodily and mental scars, a claustrophobic Frenchman, a fanatical occult investigator, a cheap hoodlum, an abusive drunkard and a woman. The woman's role is of course defined by her gender and driven by sexuality; to do otherwise would apparently defeat Lumley's understanding of storytelling.

The protagonist, the somewhat awkwardly named Sith of Thone, quickly turns out not be a truly cosmic threat but the sort of flawed, easily-understood and ultimately defeatable bogeyman of a million alien-invasion scenarios. The strange realms that the humans enter into via the many nestled Houses Of Doors turn out to have more in common with the old game show, The Crystal Maze than with, say, the dream realms of Lovecraft or Clark Ashton Smith's many magical worlds.

Ultimately, this novel doesn't hinge on a sense of horror or on its somewhat stock science fictional tropes; it's a thriller, an adventure yarn of victory against all odds, one that has more in common with the potboilers of Alistair MacLean than anything else. Although leaps of imagination sometimes caught at the edges of the awe mechanism in this reader's mind, the plodding prose, and leaden plot machinations drain those few moments of wonder of their charm and strangeness. It's not a bad entertainment, but it isn't something that needed to have been called a horror novel at all, at heart.

Baal by Robert R. MacCammon

Works well enough on its own terms; jettison expectations of originality and depth and settle for a fast-moving evil-messiah tale with many gore set pieces and a suitably vile villain and you'll be fine. Somewhat superficial research ensured that I caught all the resonances and hints quite early on, as well as a few factual errors here and there. The prose is functional but occasionally aspires to more; sometimes it gets there. Not at all bad for a first novel. But it's more gross and sickening than awe-inspiring; McCammon fails to exploit the full potential of this tale with his emphasis on viscera and profanity.

Can you tell that I'm starting to get tired of this stuff? That last review was really perfunctory.

Thursday, 31 March 2011

Tuesday, 29 March 2011

Djinn & Miskatonic

It was the proudest day of my life

When my old father showed me the letter

With the Massachusetts postmark

He said ‘Son you’re in!’

We danced around like two idiots

What else was I to do?

My whole my life my father wanted

Me to study in Miskatonic U!

Djinn and Miskatonic! Journey supersonic!

On black leathery wings, my heart sings!

Djinn and shoggoth! Can auld acquaintance be forgot?

When I get my library card I’ll learn about all those eldritch things!

I’m not like the other wizards

Unprepared idiots dying in herds

I’ve got my own magical security

A bottle djinn from old Araby

I broke the seal of Solomon

And now I command Norman

Djinn-in-waiting, faithful slave

To protect me from an early grave

Djinn and Miskatonic! Visions chthonic!

Dreaded enemy, can you beat Norman and me?

Djinn versus Mi-Go, what a way for him to go,

Now I’m taking odds against the Elder Gods

When things started to unravel, I thought I’d take a break and travel

Fell in with a girl called Cassilda, but she was too much drama

She left me in the lurch, With a dead baby in a church

I tried to re-animate the corpse, but I was arrested by the cops

Sitting there in a prison cell I rubbed that magic lamp like hell

Finally the genie re-appeared, Worse for wear as I had feared

But he broke me out of stir, then left me in a shoggoth fur

By the banks of that ancient river, strong drink poisoning my liver

Djinn & Miskatonic, vodka supersonic

You can’t outsmart the old ones, It just can’t be done

Whiskey and regret, now I try to forget

What the Mi-go sings, and the sound of leathery wings…

When my old father showed me the letter

With the Massachusetts postmark

He said ‘Son you’re in!’

We danced around like two idiots

What else was I to do?

My whole my life my father wanted

Me to study in Miskatonic U!

Djinn and Miskatonic! Journey supersonic!

On black leathery wings, my heart sings!

Djinn and shoggoth! Can auld acquaintance be forgot?

When I get my library card I’ll learn about all those eldritch things!

I’m not like the other wizards

Unprepared idiots dying in herds

I’ve got my own magical security

A bottle djinn from old Araby

I broke the seal of Solomon

And now I command Norman

Djinn-in-waiting, faithful slave

To protect me from an early grave

Djinn and Miskatonic! Visions chthonic!

Dreaded enemy, can you beat Norman and me?

Djinn versus Mi-Go, what a way for him to go,

Now I’m taking odds against the Elder Gods

When things started to unravel, I thought I’d take a break and travel

Fell in with a girl called Cassilda, but she was too much drama

She left me in the lurch, With a dead baby in a church

I tried to re-animate the corpse, but I was arrested by the cops

Sitting there in a prison cell I rubbed that magic lamp like hell

Finally the genie re-appeared, Worse for wear as I had feared

But he broke me out of stir, then left me in a shoggoth fur

By the banks of that ancient river, strong drink poisoning my liver

Djinn & Miskatonic, vodka supersonic

You can’t outsmart the old ones, It just can’t be done

Whiskey and regret, now I try to forget

What the Mi-go sings, and the sound of leathery wings…

Sunday, 27 March 2011

there is a need here, but is it the need to tell a story?

Comments from an aspiring writers' forum:

'I am creating my own species...'

'I have created my own world but at present I only explore a small portion of it...'

'I don't have children but I feel like my characters are my children...'

'I love escaping to my world and my characters and I hope my readers will too...'

'I am creating my own species...'

'I have created my own world but at present I only explore a small portion of it...'

'I don't have children but I feel like my characters are my children...'

'I love escaping to my world and my characters and I hope my readers will too...'

Friday, 25 March 2011

'Memento Mori' by Samuel Menashe

this skull instructs

me now to probe

the socket bone

around my eyes

to test the nose

bone underlies

to hold my breath

to make no bones

about the dead

Thursday, 24 March 2011

THE NAMELESS BY RAMSEY CAMPBELL

I've never been altogether satisfied with the few novels by Ramsey Campbell that I've read. He tends to be subtle to the point of reticence, a quality which can work within the concentrated span of a short story, and often does, but which seems to lead to horror novels that shield themselves from the consequences of their own central conceits. I'm not a gore-hound, but I do like a build-up of weird atmosphere and if possible a truly bizarre irruption of the numinous into a horror story. That's probably why I like writers like Thomas Ligotti, Laird Barron and W.H. Pugmire, all of whom are masters of atmosphere, weirdness and outré imagery in their own diverse ways.

Campbell is sort of the flagbearer of modern British horror; he is also a devotee of Lovecraft, even a member of the extended Lovecraft Circle through his early correspondence with August Derleth, who published a 15-year-old Campbell's first essays at horror, written in a thoroughly Lovecraftian mode. As such, Campbell can be seen as heir to the two most significant strands of Anglophone horror - the tale of cosmic terror as epitomised by H.P. Lovecraft's work and the more inward-looking, supernaturalist horror of vintage practitioners from the British Isles, such as Algernon Blackwood or Arthur Machen.

And the novel at hand has elements of both; there is an early encounter with a spiritualist who provides important clues, and there are run-ins with the world of occult societies later on. But Campbell also draws on the cosmic forces Lovecraft invokes, as well as the many tutelary entities and nameless cults that gravitate to them. He does this in a manner that is profoundly more assured than his earlier Mythos fiction - he does not attempt to use any of the paraphernalia of Yog-Sothothery or tie his terrors in with Lovecraft's. But there is a broadening of scale towards the end of the novel that definitely owes something to the Lovecraftian vision.

Campbell relates his cults and forces to the currents of his times, however, tying them in with the murder cults of drugged-up hippies, referring directly to the Manson family and to the extended new-age cults of the modern western world. So far, so good.

Campbell also takes the time to build a foreground narrative that is grounded in well-rounded, realistic characters. He also has a knack for describing cityscapes and passing scenery with original, sharp and memorable metaphors; one wishes that he was just as inventive and captivating when it came to describing the the weird stuff, the business we're here for. Not that he is bad at all sustaining and ever so slowly building an atmosphere of understated foreboding, but part of the problem we have here is what I've noted in works by SF and fantasy writers who seem to want to normalise toward some sort of mix of either airport thriller style or lit-fic. It's probably laudable to bring in the ice-pick similes of the Booker set and the character focus of the patented page-turner if this helps raise the specific generic values of the novel, and it does to an extent. But in the process, something of the impact of the horrific core of this novel is deferred and even diluted, although not as badly as in the previous novels I've read by Campbell. But everytime he captures a vista glimpsed down a city street or out of a moving tale with a limpid phrase, I can't help but wish that he had expended a little more stylistic fireworks on the strange entities, cultists and rituals that we occasionally catch up with in between all the well-framed character development. Fortunately, the development of the foreground story always drives the plot forwards, so we do get to the horrific bits eventually. And we do get a good conclusion - some truly terrifying and cosmic intimations, a resolution that is redemptive and upsetting at the same time and an ending that wraps up without explaining more than is needed (this is a key factor in horror, where any amount of imagery is fine, but too much explanation can kill the magic).

With all the reservations I've expressed, I found this novel gripping precisely because Campbell made me care about the characters; but I was left with perhaps less of a feeling of having been brought face to face with a vision of true strangeness and threat than I would have wished. I would have been glad to learn a little more about the demented philosophy of the nameless, to spend a little more time in their founder's company, to have a little more of a glimpse of the darker power that the cult served, but Campbell only gives us access to just as much as is needed to keep the foreground narrative on track. Still, what there is, is effective and disturbing, so all in all mark this one up as a definite win for Campbell.

I do have one strong objection though; at one point, Campbell shows us a female character stripping down to her underwear; sure enough, she is marked for destruction. In a certain kind of storytelling, a woman's nakedness is always a precursor to her extinction. This is such a cliche of the worst kind of schlock that I'm a little taken aback Campbell didn't even realise what he was doing here.

I'd also like to highlight how well Campbell uses an urban setting to serve as a locus of horror, with the crowds, noise and pockets of urban blight found in a big city all contributing to create a nurturing environment for evil.

In 1999, a Spanish film entitled Los Sin Nombre was made as a partial adaptation of this novel; I'll be reviewing that in my next update.

Campbell is sort of the flagbearer of modern British horror; he is also a devotee of Lovecraft, even a member of the extended Lovecraft Circle through his early correspondence with August Derleth, who published a 15-year-old Campbell's first essays at horror, written in a thoroughly Lovecraftian mode. As such, Campbell can be seen as heir to the two most significant strands of Anglophone horror - the tale of cosmic terror as epitomised by H.P. Lovecraft's work and the more inward-looking, supernaturalist horror of vintage practitioners from the British Isles, such as Algernon Blackwood or Arthur Machen.

And the novel at hand has elements of both; there is an early encounter with a spiritualist who provides important clues, and there are run-ins with the world of occult societies later on. But Campbell also draws on the cosmic forces Lovecraft invokes, as well as the many tutelary entities and nameless cults that gravitate to them. He does this in a manner that is profoundly more assured than his earlier Mythos fiction - he does not attempt to use any of the paraphernalia of Yog-Sothothery or tie his terrors in with Lovecraft's. But there is a broadening of scale towards the end of the novel that definitely owes something to the Lovecraftian vision.

Campbell relates his cults and forces to the currents of his times, however, tying them in with the murder cults of drugged-up hippies, referring directly to the Manson family and to the extended new-age cults of the modern western world. So far, so good.

Campbell also takes the time to build a foreground narrative that is grounded in well-rounded, realistic characters. He also has a knack for describing cityscapes and passing scenery with original, sharp and memorable metaphors; one wishes that he was just as inventive and captivating when it came to describing the the weird stuff, the business we're here for. Not that he is bad at all sustaining and ever so slowly building an atmosphere of understated foreboding, but part of the problem we have here is what I've noted in works by SF and fantasy writers who seem to want to normalise toward some sort of mix of either airport thriller style or lit-fic. It's probably laudable to bring in the ice-pick similes of the Booker set and the character focus of the patented page-turner if this helps raise the specific generic values of the novel, and it does to an extent. But in the process, something of the impact of the horrific core of this novel is deferred and even diluted, although not as badly as in the previous novels I've read by Campbell. But everytime he captures a vista glimpsed down a city street or out of a moving tale with a limpid phrase, I can't help but wish that he had expended a little more stylistic fireworks on the strange entities, cultists and rituals that we occasionally catch up with in between all the well-framed character development. Fortunately, the development of the foreground story always drives the plot forwards, so we do get to the horrific bits eventually. And we do get a good conclusion - some truly terrifying and cosmic intimations, a resolution that is redemptive and upsetting at the same time and an ending that wraps up without explaining more than is needed (this is a key factor in horror, where any amount of imagery is fine, but too much explanation can kill the magic).

With all the reservations I've expressed, I found this novel gripping precisely because Campbell made me care about the characters; but I was left with perhaps less of a feeling of having been brought face to face with a vision of true strangeness and threat than I would have wished. I would have been glad to learn a little more about the demented philosophy of the nameless, to spend a little more time in their founder's company, to have a little more of a glimpse of the darker power that the cult served, but Campbell only gives us access to just as much as is needed to keep the foreground narrative on track. Still, what there is, is effective and disturbing, so all in all mark this one up as a definite win for Campbell.

I do have one strong objection though; at one point, Campbell shows us a female character stripping down to her underwear; sure enough, she is marked for destruction. In a certain kind of storytelling, a woman's nakedness is always a precursor to her extinction. This is such a cliche of the worst kind of schlock that I'm a little taken aback Campbell didn't even realise what he was doing here.

I'd also like to highlight how well Campbell uses an urban setting to serve as a locus of horror, with the crowds, noise and pockets of urban blight found in a big city all contributing to create a nurturing environment for evil.

In 1999, a Spanish film entitled Los Sin Nombre was made as a partial adaptation of this novel; I'll be reviewing that in my next update.

Tuesday, 22 March 2011

Bevar Sea @ Trendslaughter 2011

Second show. Seemed to go well.

That's me in the baby-blue The Beatles t-shirt.

Our setlist:

The Smiler

God's Wounds

Abishtu

Into The Void (Black Sabbath cover)

Mono Gnome

Green Machine (Kyuss Cover)

Universal Sleeper

We played for about an hour. The other bands were a young thrash act called Culminant, Gorified, the goregrind band, veteran doom-deathers Dying Embrace and Orator, a death/thrash band from Bangladesh.

That's me in the baby-blue The Beatles t-shirt.

Our setlist:

The Smiler

God's Wounds

Abishtu

Into The Void (Black Sabbath cover)

Mono Gnome

Green Machine (Kyuss Cover)

Universal Sleeper

We played for about an hour. The other bands were a young thrash act called Culminant, Gorified, the goregrind band, veteran doom-deathers Dying Embrace and Orator, a death/thrash band from Bangladesh.

Friday, 18 March 2011

Sing, oh muse, and the days when she does. When words typed across across a glowing screen start becoming people, places, events, when whispers in my head start start to sing and characters emerge from the mist with faces and histories and voices. When the heat is white and casts light across pages that line themselves up to be written. These days are a part of the reason why.

Thursday, 17 March 2011

Wednesday, 16 March 2011

This is probably not as big a deal as it felt like when I first heard of it, but this story got a mention here. I'm not sure how many horror stories were published last year, but, in short, this means mine was somewhere in the top 600 or so, although not really in the top 100 or 50 or 10.

Here's something that caught my eye in an interview with horror writer John Langan:

A commenter noted that I used the term 'kitsch' in various versions all over my earlier wordsplurge. And it's an important part of my point too. The less you delve into the medium you want to be a part of , the less of a yardstick you have. Jeffrey Archer only seems great until you read John Buchan. The Harry Potter books only seem dazzlingly different and original until you've tried Earthsea, Books Of Magic and the odd Jane Yolen novel. That terrible Year Of The Tiger book I reviewed last year only seems like literature until you've read some Atwood or Nabokov. Kitsch has its place (I am told) but until you also have an understanding of genuine artistry and find a permanent place for it in our aspirations and affections, no amount of ironic or faux-naive posing will change the fact that you have no taste.